It is a big pedagogic change from a traditional classroom from a space dominated by desks in rows to a space suiting 21st century learning that incorporates digital, mobile, independent and social collaboration (Beetham & Sharpe, 2013, Radcliffe et. al. 2008).

This disruption can be exciting or distressing, depending on how much control people using the space feel they have in the situation. Before you start to make a change in the learning space, consider including those people who will be experiencing the change in the decision making process.

How can you share control and increase their agency and the long term learning benefit? This article draws from some research I have conducted in Queensland schools, where school principal Emma, and teacher Kathryn involved a Year 4 class in designing their new learning space (Willis, 2014).

Quite often learning spaces are designed without teachers or students having any input. Instead of being empowering, these new learning spaces can cause teacher stress about how to teach in the new conditions, and confusion for students (Wilks, 2009).

Emma noted “even gorgeous schools I went to recently, most of the classrooms were rows, facing the front.” To make the most of the financial investment, the change leader also needs to consider the emotional and cognitive investment. This was the successful process Emma and Kathryn used.

1. Creating Cultural Readiness

In this school collaboration and consultation between leaders and staff was a regular occurrence. Emma had noted, “In most schools the Deputy Principal just rings up and orders furniture.

Teachers and students don’t know what they are getting or why they are getting it, which means they won’t value it and won’t know how to use it.” So when Emma invited Kathryn to participate, and explained why, Kathryn was ready to try something new.

2. Creating a Practical Vision

Emma communicated the vision for pedagogic change in personal and practical ways early in the process. Emma and Kathryn visited BFX. Kathryn was able to see and touch furniture and talk with an industry expert who had collaborated with many schools.

Kathryn took away a scaled map of how the classroom might look in the space with her preferred furnishings.

The experience of making the vision of a new learning space tangible early in the process enabled Kathryn to imagine new possibilities and feel supported in what both an exciting and a scary responsibility.

3. Supporting the Translation of the Vision to a Strategic Curriculum Plan

Kathryn then developed a curriculum plan using the Learning by Design framework (Kalantzis & Cope, 2005) through which students are encouraged to be meaning makers in a creative and dynamic process “through which the meaning-makers remake themselves” (Cazden et al, 1996. p. 74).

Leaving the plan open for student input was a new experience for Kathryn as she usually planned each week meticulously and “I have had to let go of that. It was a necessary thing to happen, but it did worry me.”

Emma worked regularly alongside Kathryn in the classroom as their plans for including the students in the participatory design were enacted.

4. Collaborating with Students as Designers

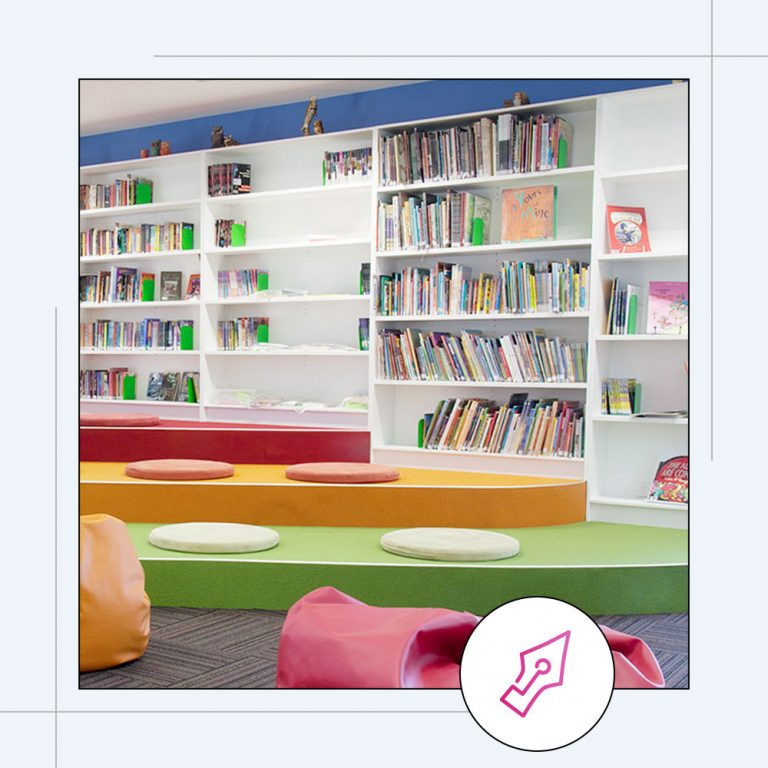

Children imagine learning spaces that focus on fun, colour, light and connections to nature and technology to enable learning that is cooperative, social and actively engaged with the world (Bland, 2011).

A Technology unit called ”Designs for Learning” structured the students’ collaboration. Students used digital cameras, concept mapping software and collaborative charts to capture, share and reflect on their learning.

Some of the curriculum activities included: Creating a dream bedroom and building a scale model in a shoebox. They then appraised their design, and invited parents to an exhibition of their work.

Researching about 21st century learning, reading magazine articles and design articles on the internet, working in groups to identify what implications these principles would have for learning spaces.

Completing an online quiz to determine their preferred learning style and environment (www.learningstyles.net), and discussing the class profile in learning environment preferences.

Researching the psychological impact of colour on emotion and developed appraisal criteria for positive learning spaces.

Imagining what their dream classroom would look like, feel like and sound like. These ideas were captured in a wordle and drawings they then explained features to peers. The class then synthesised the results with previous research, to develop a class vision for learning.

Visiting a furniture factory to see how furniture is made, and seeing and touching what types of classroom furniture they could choose from.

Reviewing various carpet and furnishing sample books. The students worked in teams, excitedly feeling textures, putting sticky note flags on preferred items, and justifying choices to one another before making decisions about their preferences.

Creating floor plans using Google Sketchup, and then discussing how to resolve the dilemmas that emerged when the scaled models showed that not all of their desired furnishings might fit.

Interviewing younger students to ask about their preferred learning spaces, and older students, asking about their learning in their renovated spaces, so that they were not just meeting their own preferences.

5. Supporting transitions towards collaborative learning

Emma supported Kathryn in the initial stages by making frequent classroom visits to talk with the students about their design work, sometimes co-teaching the lesson, or working with a small group.

Emma modelled how to establish behavioural expectations while also moving away from a teacher-centered delivery.

By mid year, there were significant changes in Kathryn’s pedagogic practices, and student patterns of behaviour, moving from a teachercentered delivery, towards a supportive learner centered, collaborative classroom, and students were able to use the design language of collaboration, and flexibility to explain their learning preferences.

6. Sustaining Change through Reflecting, Reframing and Responding

As a collaborative leader, Emma worked to understand the perspectives of her teachers, and through inquiring conversations reposition or reframe troubling situations so teachers or students were able to feel greater control.

7. Ongoing brokering of construction processes

Emma was actively involved in liaising with the various supervisors and local contractors responsible for various parts of the building reconstruction that was also occurring.

She estimated that leading this design process with the children, working with the teachers in conversations about planning, pedagogy and learning data, and managing the budget and building took up “at least half – more probably” of her time as Principal. Considering this emotional and cognitive investment of her time as a leader, were the outcomes worth it?

In committing to this shared learning experience, Emma wanted more learners to say about themselves, “I am a person who can make things happen.”

Emma and Kathryn made it socially safe for students to “speak back regarding what they consider to be important and valuable about their learning” (Smyth 2006. p. 282).

In the process of speaking up and speaking back to those in power, the students developed greater confidence in themselves as decision makers in the schooling system, and increased agency, that is “the ability to exert control over and give direction to one’s life”

Biesta & Tedder, 2007. p. 134 Tweet

The students also increased their understanding of their own learning styles, empathy for others, and a shared responsibility for learning as a group.

When students and teachers are involved in imagining what their new learning spaces may look like prior to their occupancy, it is a significant opportunity for teachers and students to imagine how they might use the space, and consider alternative routines and reimagine old practices (Bland, Hughes & Willis, 2013).

In this project, the teachers and learners experienced a supportive and transformative change in their learning even before they began learning together in their newly designed learning space.